The Health Professions Act includes provisions regarding sexual misconduct and sexual abuse of patients by health professionals. This guide discusses the issue of sexual abuse and sexual misconduct, highlights principles of trauma-informed practice, and reviews the requirements established in legislation.

Protecting Patients from Sexual Abuse or Misconduct GuideSexual misconduct and sexual abuse of patients by their health-care providers undermines the public’s trust in health professionals and the health system at large and can profoundly effect the health and wellbeing of those who have been abused. This type of conduct towards patients is not and has never been acceptable within physiotherapy practice.

The Health Professions Act (HPA) has addresses concerns about sexual misconduct and sexual abuse of patients by defining prohibited behaviours and establishing mandatory penalties when sexual abuse or misconduct occurs.1 The Health Professions Act of Alberta also requires regulatory bodies, including the College of Physiotherapists of Alberta, to establish measures for preventing and addressing sexual abuse and sexual misconduct towards patients by regulated members. This guidance document is one of many resources designed to increase registrant understanding of the issue and fulfill this requirement.

Since these legislative requirements came into force in 2019, there has been considerable discussion regarding the issue of sexual abuse and sexual misconduct towards patients by regulated health professionals. Although the requirements of legislation are unchanged from 2019, the physiotherapy community’s collective understanding of the issue and how it arises within physiotherapy practice has evolved. This updated guidance document builds upon the College’s prior guidance, existing resource documents, and understanding of factors that contribute to complaints of sexual abuse and sexual misconduct.

Regulators, employers, managers, supervisors, physiotherapists, and their peers all have a role to play in addressing this important issue.

Why this matters

Prevalence of sexual violence

- Research suggests that approximately 33% of females and 16% of males will experience sexual assault within their lifetime.2

- It has also been estimated that 50% of girls and 33% of boys will experience sexual abuse (defined as exposure of a child to sexual contact, activity or behavior – including exhibitionism, exposure to pornography, sexual touching or sexual assault) by the time they are 16 years old.2,3

- The prevalence of experiences of sexual violence among Indigenous persons, racialized individuals, and members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community is understood to be even higher.4,5

- An individual’s previous experience of sexual violence is associated with increased health concerns and health seeking behaviour.6,7,8

- Physiotherapists are members of a “touching profession.” The risk of triggering a trauma response from a patient while providing treatment is greater than that for members of professions that do not employ physical touch as part of their practice.

- The College has received a number of complaints related to allegations of sexual abuse and sexual misconduct since changes were made to the Health Professions Act in 2019.

These factors combine to make issues of sexual violence and trauma-informed practice pressing concerns for physiotherapists. It is certain that you, whether you know it or not, work with survivors of sexual violence on a regular basis.

Recognizing this fact, it is imperative to take steps to address health-care delivery related concerns relevant to survivors of sexual violence, such as employing trauma-informed practice, to prevent harm to patients and maintain public trust in physiotherapists and the services they provide. Equally essential are efforts to reflect upon, modify, and manage clinician behaviour, recognizing that it is also true that clinicians may engage in conduct, behaviour, or remarks (intentional or otherwise) which patients and others perceive as inappropriate conduct that is sexual in nature.

The Alberta Physiotherapy Context

In 2023, the College undertook a review of the themes seen in complaints related to Sexual Abuse and Sexual Misconduct.

Four themes were identified:

- Lack of awareness of professional requirements

- Communication

- Consent

- Culture and Sensitive Practice

In relation to professional requirements, some of the recurring gaps in awareness relate to knowledge of:

- Prohibited behaviours

- Duration of the therapeutic relationship

- Sanctions that apply to findings of sexual abuse and sexual misconduct

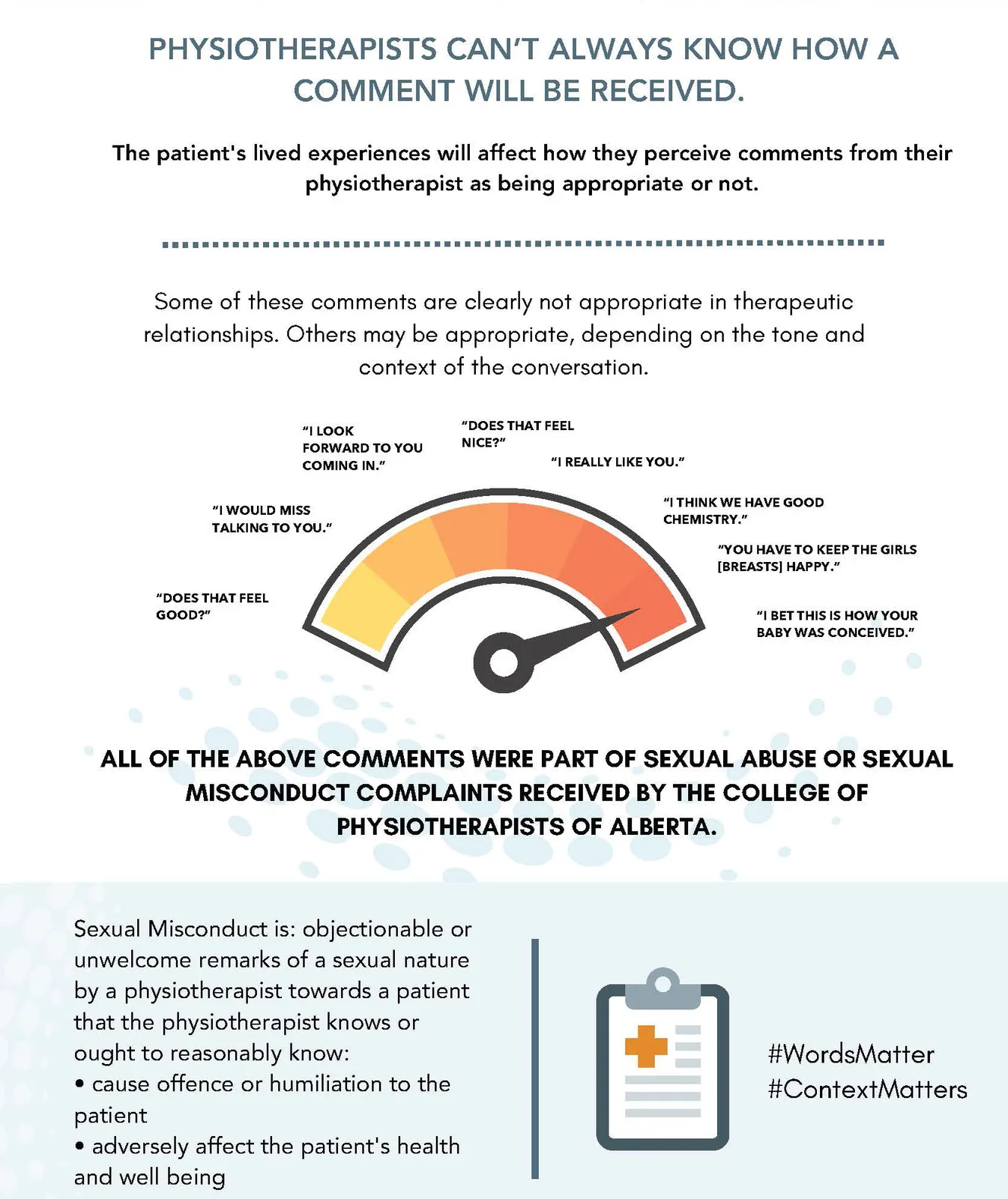

In relation to communication, past professional conduct matters highlight that:

- Physiotherapists do not always know how a comment will be received.

- There is a need for attention and conscious effort to view comments through the eyes of the patient.

- The need for communication and expectation setting with patients about what a physiotherapy assessment or treatment involves, including the use of touch and potential need to change clothing or otherwise expose the area assessed or treated.

In relation to consent, recurring gaps in awareness include:

- Patient and public expectations for consent for touch, clothing adjustment, and draping.

- The meaning of and expectations regarding ongoing consent.

- Actions necessary to demonstrate that consent was informed.

Finally, in relation to culture and sensitive practice, physiotherapists must:

- Employ trauma-informed practice with all patients and in all practice settings to avoid re-traumatizing survivors.

- Be alert to the norms and culture of their patients and what the patient brings to the table in terms of culture, norms, and unstated expectations regarding physiotherapy.

- Remember that the patient may not know what physiotherapists do or understand what constitutes typical physiotherapy practice, including physical touch and the need to directly see the body area in question.

- Reflect on their own culture and norms of conduct, adjusting their behaviour to meet the patient’s and society’s expectations, while maintaining high standards of professionalism.

Given that the College consistently receives complaints categorized as sexual abuse and sexual misconduct, it is imperative that all physiotherapists adhere to the rules of practice and remain attentive to the aspects of practice within their control.

Knowledge of the rules of practice is imperative, as is a shared effort among physiotherapy colleagues and supervisors to support good practice and address questionable behaviour before it reaches the level of a breach of the standards. To support their colleagues and supervisees, all physiotherapists need to know and understand the legislation and requirements of the standard and consider how these apply to their practice.

Alberta’s Health Professions Act contains provisions related to sexual abuse and sexual misconduct.1 The purpose of these provisions is to identify, eliminate, and properly address sexual abuse and sexual misconduct committed by regulated health professionals towards their patients.

Legislated definitions of sexual abuse and sexual misconduct are specific in stating that the conduct is prohibited when the conduct occurs by a regulated member towards a patient.

Alberta health profession regulatory bodies are required to define for the profession regulated within that profession’s Standards of Practice the definition of patient. As a result, the definition of patient differs between regulated health professions.

Who is a physiotherapy patient?

You must be aware of the College of Physiotherapists of Alberta definition of a patient found in the Sexual Abuse and Sexual Misconduct Standard of Practice.

An individual is a patient of a physiotherapist when they are a recipient of physiotherapy services and a therapeutic relationship is formed. This occurs when a physiotherapist has engaged in one or more of the following activities:

- Gathered clinical information to assess an individual

- Contributed to a health record or file for the individual

- Provided a diagnosis

- Provided physiotherapy advice or treatment

- Charged or received payment from the individual or third party on behalf of the individual for physiotherapy services provided

- Received consent from an individual for recommended physiotherapy services9

A patient is deemed discharged and no longer a patient if there have been no physiotherapy services provided for one year (365 days.)9

What conduct is prohibited?

Sexual abuse means the threatened, attempted or actual conduct of a regulated member towards a patient that is of a sexual nature and includes any of the following conduct:

- sexual intercourse between a regulated member and a patient of that regulated member;

- genital to genital, genital to anal, oral to genital, or oral to anal contact between a regulated member and a patient of that regulated member;

- masturbation of a regulated member by, or in the presence of, a patient of that regulated member;

- masturbation of a regulated member’s patient by that regulated member;

- encouraging a regulated member’s patient to masturbate in the presence of that regulated member; or

- touching of a sexual nature of a patient’s genitals, anus, breasts or buttocks by a regulated member.1 HPA Section 1(1)(nn.1)

Sexual abuse of a patient can happen in the practice setting or after hours. The key is whether all the elements in the definition of sexual abuse are present:

- A regulated health professional

- A patient of the regulated health professional

- Conduct described as sexual abuse in the Act

The definition of sexual misconduct found in the Health Professions Act is “Any incident or repeated incidents of objectionable or unwelcome conduct, behaviour or remarks of a sexual nature by a regulated member towards a patient that the regulated member knows or ought reasonably to know will or would cause offence or humiliation to the patient or adversely affect the patient’s health and well-being but does not include sexual abuse.”1 HPA Section 1(1)(nn.2)

Physiotherapists do not always know how a comment will be received by their patient.

The term sexual nature is not defined in the Health Professions Act, however HPA Section 1(1)(nn.3) specifies that “‘sexual nature’ does not include conduct, behaviour, or remarks that are appropriate to the service provided.”1

Unprofessional conduct

Sexual abuse and sexual misconduct are two specific types of unprofessional conduct under the Health Professions Act. How misconduct is classified—as sexual misconduct, sexual abuse, or unprofessional conduct generally is important because there are special provisions in the Act (including mandatory sanctions) that apply only to sexual misconduct and sexual abuse as defined by the legislation.

Penalties

The Health Professions Act1 sets out mandatory penalties (sanctions) for findings of sexual abuse and sexual misconduct.

IF a hearing tribunal finds that a physiotherapist’s conduct constitutes unprofessional conduct based in whole or in part on sexual abuse, the hearing tribunal must order the cancellation of the investigated person’s practice permit and registration (HPA Section 82(1.1)(a). The cancellation of the investigated person’s practice permit is permanent, as the individual is not eligible to apply for reinstatement (HPA Section 45(3)(a). The result is a lifetime ban on the ability to practice physiotherapy in the province of Alberta.

IF a hearing tribunal finds that a physiotherapist’s conduct constitutes unprofessional conduct based in whole or in part on sexual misconduct, the hearing tribunal must order the suspension of the investigated person’s practice permit for a specified period of time (HPA Section 82(1.1)(b)).

IF a physiotherapist’s practice permit is suspended or cancelled, the Registrar must provide this information to all physiotherapy regulators in Canada (HPA Section 119). Although a finding of sexual misconduct is less egregious than a finding of sexual abuse, both penalties are significant and will affect the physiotherapist’s professional standing, employability, and future. Keep in mind that when physiotherapists move and attempt to register in a different province or country, it is standard practice for the other jurisdiction to obtain information from the College of Physiotherapists of Alberta about the physiotherapist’s regulatory history. If there is a history of findings related to sexual misconduct or sexual abuse, the Health Professions Act (HPA Section 119) requires that we release the information.

In other words, this history will move with the physiotherapist. It is up to the new province or country to determine if they can and will grant the physiotherapist a license to practice in light of their regulatory history.

Publication

Colleges are required to publish information about their current and former registrants on their website. This includes indefinite publication of information about conduct findings or conditions placed on registrants’ practice permits because of sexual abuse or sexual misconduct (HPA Section 135.92(2)(e)).

Patient relations program

Colleges must provide education and training for registrants and college staff on preventing and addressing sexual abuse and sexual misconduct. The patient-relations program must also provide information to Albertans to help them understand the College’s complaints process. Colleges must provide funding for treatment and counselling for patients who have filed a complaint alleging sexual abuse or sexual misconduct by a registrant of the College and must ensure that complainants have greater participation in the investigation and hearings process (HPA Part 8.2 Sections 135.6 -135.9).

Mandatory reporting

The Act requires that employers, registrants, and other regulated health professionals report situations where they have reasonable grounds to believe that a health professional has sexually abused or engaged in sexual misconduct of a patient.1 The mandatory reporting makes sure that sexual abuse and sexual misconduct are identified and properly addressed (HPA Sections 57(1.1) and 127.2(1)).

Physiotherapists are also required to report to the Registrar as soon as reasonably possible if they have been charged with an offence under the Criminal Code of Canada. This includes reporting any charges of sexual offences (HPA Section 127.1).

The therapeutic relationship is the foundation of all patient – professional interactions. The term therapeutic relationship “refers to the relationship that exists between a physiotherapist and a patient during the course of physiotherapy services. The relationship is based on trust, respect, and the expectation that the physiotherapist will establish and maintain the relationship according to applicable legislation and regulatory requirements and will not harm or exploit the patient in any way.” Specific to sexual abuse and sexual misconduct, a healthy therapeutic relationship and attention to its foundational elements can help to prevent instances of sexual abuse or sexual misconduct.

Components of therapeutic relationships:

- Respect, trust, and sensitivity

- Duty of care

- Professional boundaries

- Power

Therapeutic relationships are reciprocal relationships that are caring, clear, positive, and professional.10 Therapeutic relationships are based on respect and trust and rely upon your commitment to fulfill your duty of care and maintain appropriate professional boundaries with patients.10

Respect, Trust, and Sensitivity

Respect for the patient’s identity, beliefs, and values, is required to develop a therapeutic relationship. You don’t have to agree with the patient, but you do have to accept the patient’s right to make their own decisions and hold their own beliefs. It’s essential that your patients trust you to meet their needs, act in their interests, and to fulfill your duty of care. Demonstrating respect for your patients, particularly patients whose identity, beliefs, and values differ from your own, can help to foster that trust. Seeking to understand your patient’s perspective, adjusting your approach to address your patient’s needs, and acting with honesty and integrity fosters a trusting therapeutic relationship.

Trust and respect are protected by sensitivity. Be aware of and sensitive to your patients’ vulnerability, especially in situations involving disclosure of personal information, close physical proximity, touch, and varying degrees of undress necessary to provide physiotherapy services. As stated earlier, you need to work to view your comments and actions through the eyes of the patient. This includes considering the patient’s perspective with this vulnerability in mind and considering how a patient’s perception of their own vulnerability may affect how a comment or action is perceived.

Sensitivity also helps you to maintain appropriate professional boundaries and remain alert to boundary erosion or boundary blurring.

The therapeutic relationships guide for Alberta physiotherapists provides additional information about developing the therapeutic relationship, maintaining professional boundaries, and avoiding boundary violations.

Duty of Care

Duty of care, or fiduciary duty, is the duty to act in the patient’s best interest. Your duty of care means that you have an obligation to your patients to act with reasonable care and skill when providing care. Duty of care also means that you are obliged to act in good faith towards the patient.9

Specific to sexual abuse and sexual misconduct, do not use your professional role as a means of pursuing personal relationships with patients.9 When physiotherapists develop personal relationships with patients rather than maintaining professional boundaries, they fail to fulfill their duty of care to the patient.

You need to be mindful of your own mental health and need for personal support. You need to ensure that your personal needs for support and friendship are fulfilled outside of the practice setting and through personal relationships with colleagues, rather than through development of personal relationships with patients.

Make a clear distinction between your professional role and your personal life.11

Professional Boundaries

Professional boundaries refer to the accepted social, physical or psychological space between people.9,12 Boundaries create the therapeutic or professional distance between the health professional and the patient and help to clarify the roles and expectations of both the patient and the regulated health professional.12

When developing therapeutic relationships, you need to balance maintaining professional boundaries with self-disclosures used to support the development of the therapeutic relationship.10 Used intentionally, self-disclosures can support the therapeutic relationship; however, self-disclosures that undermine professional boundaries or which are made for the purpose of developing personal relationships must be avoided. Self-disclosures should serve a specific therapeutic purpose.

Power

It is generally understood that power imbalance is at the root of sexual violence.13 Your unique knowledge and skills, and access to the patient’s private information gives you inherent power within therapeutic relationships.11 This makes your patient vulnerable. You must be mindful of this imbalance of power, and work to reduce it as much as possible. There are many strategies to do so, including strategically positioning yourself during conversations, sharing information and decision-making, and using plain language to ensure patients understand the information you provide.

However, despite efforts to share or equalize power, you need to recognize that power is never completely balanced. This means that you must remain vigilant to situations where power may be misused or may affect an interaction with a patient.

Power and Sexual Relationships

In Canada, sexual relationships occur in the context of free, informed, voluntary consent. According to the Government of Alberta, “consent cannot be given if the perpetrator abuses a position of trust, power, or authority.”14 If valid consent is not in place, a sexual interaction may be considered assault or abuse.

Even if a patient “agrees” to a sexual interaction with a physiotherapist, they are not able to consent to it. By prohibiting sexual interactions between health professionals and their patients, the Health Professions Act makes it clear that a patient’s agreement to a sexual interaction is not considered ”consent” due to the inherent abuse of a position of trust, power, and authority by the health professional.15

Sexual relationships with patients are prohibited for 365 days from last physiotherapy treatment (the duration of the therapeutic relationship).9

Valid, informed consent is essential when providing physiotherapy services. Issues related to consent are often an element of the complaints and concerns received by the College regarding the actions of physiotherapists, whether those actions relate to sexual misconduct, sexual abuse, or to other actions of the physiotherapist.

The Consent Guide for Alberta Physiotherapists provides additional information about consent, including underlying principles, an overview of the consent process, and common clinical considerations.

To be considered valid, consent needs to adhere to the following basic principles:16

- Autonomous: The ethical principle of autonomy or self-determination underpins the obligation to obtain informed consent.

- Voluntary: Consent is not valid if obtained by coercion, undue influence, or intentional misrepresentation.

- Informed: Consent is not valid if it is based on incomplete or inaccurate information.

- Capacity: Consent is only valid when the person providing consent has the capacity to do so.

- Service Specific: The patient provides consent to a specific physiotherapy service after being informed of the risks and benefits of the proposed physiotherapy service.

- Provider Specific: The person providing the service needs to obtain consent from the patient. Consent to receive physiotherapy services from one person does not mean they have consented to services from another person.

- Format: Consent can be obtained in writing (e.g., signed consent form) or verbally.

- Documented: Consent must be documented.

- Right to Refuse: Patients have the right to refuse services or to withdraw previous consent.

Relevant to discussions of sexual abuse and sexual misconduct, you must clearly communicate what the assessment or treatment involves (in terms of your actions) while assessing or treating the patient, including contact with the patient’s body or adjustments of the patient’s clothing. You must also explain why that action is needed and the patient’s options if they do not agree to your proposed actions – including altering the assessment or treatment process to avoid the unwanted contact, or having a support person of the patient’s choosing present to observe the assessment or treatment.

The presence or absence of voluntary, informed patient consent can be critical to how your actions are understood, and to allegations of sexual abuse or sexual misconduct. For example, if you adjust a patient’s clothing to observe an injured area without explaining what you are doing and why, this could lead to allegations of misconduct.

Ongoing Consent

Ongoing, informed consent is a basic requirement and expectation for all health services. Patients have the unalienable right to determine what happens to their body, and to change their minds and withdraw consent at any time. Given that physiotherapy assessment and treatment involves changes to patient and provider positioning, patient contact, and patient draping occurring throughout the course of an assessment or treatment, consent must also be ongoing in nature. Ongoing consent is important for establishing that the patient understands what is happening or about to happen and continues to agree.

In addition, ongoing consent is an essential element of trauma-informed practice.

You need to know that you have the patient’s permission to proceed with an assessment or treatment plan. If that permission is ever in question, you need to pause and reaffirm that consent is in place.

This does not mean that you are expected to complete an extensive discussion of the patient’s perspectives and values, the benefits, and risks of the physiotherapy services each time a patient receives physiotherapy services. It does mean that you need to explain what you are doing and why as you work through the assessment or treatment and confirm that the patient agrees to continue. It also means that you need to pay attention to the patient’s verbal and non-verbal responses and to signs that the patient may not agree or is withdrawing consent.

The amount of discussion required when establishing initial consent and confirming ongoing consent is context specific and depends upon the patient, physiotherapist, setting, and services proposed. If in doubt, err on the side of over communicating.

Applied to the practice context, this means that you must:

- Confirm that the patient understands what they are consenting to.

- Explain what you are going to do and the reasons why.

- Check that the patient understands, for example, by having them explain the plan in their own words.

- Avoid technical language or jargon.

- Obtain consent to each aspect of treatment.

- Consent to one aspect of an assessment or treatment does not mean the patient has consented to other assessments or treatments.

- Ensure consent is in place on an ongoing basis.

- Check with the patient regularly to ensure that they continue to consent.

- Tell them that they have the right to change their mind at any time.

- Watch for non-verbal signs that the patient is uncomfortable, which may include:

- Physically withdrawing

- Tensing of hands or body

- Shallow respirations

- Decreased responses to questions

- Appearing to “zone out” or cease to attend to the interaction

Effective communication and actions to confirm ongoing informed consent can help improve patient comfort and satisfaction with the physiotherapy services received and prevent misunderstandings.

Developing trust, navigating the therapeutic relationship, obtaining valid informed consent, and ensuring ongoing consent is in place, all rely on effective communication. Effective communication is communication that is clear, understood, and provides neither more nor less information than necessary.

Although physiotherapy practice can be technical in nature, when communicating with patients you need to adjust the terminology you use, employing plain language, and avoiding technical terms and professional jargon. Regardless of the patient’s education, health literacy, or background, plain language facilitates understanding and informed decision making. Plain language is especially important when people are under stress, including the stress of requiring health services, and when working with patients for whom English is not their first language.

Clear communication helps to mitigate against sexual abuse and sexual misconduct by ensuring that all parties understand what will occur during a physiotherapy assessment or treatment and that valid informed consent is in place.

Communication that is unrelated to the delivery of physiotherapy services can be important for developing rapport with the patient, whether that is a discussion of the local sports team, the weather, current events, hobbies you and the patient have in common, or your pets. These discussions can help to enhance the therapeutic relationship. However, they can also become problematic if they result in boundary blurring.

As already mentioned, physiotherapists do not always know how a comment will be received by their patient. During the delivery of physiotherapy services, you may have relatively consistent language that you use when explaining assessment procedures or treatment options. Equally, when interviewing a patient about their history or current symptoms, you are likely to be attentive to their verbal and non-verbal communication because it is related to the delivery of services.

When engaged in communication that is unrelated to the delivery of services, it is equally essential to be attentive to both comments made and non-verbal aspects of communication. You need to pay attention to these informal conversations and work to view informal comments through the eyes of the patient. Arguably, these are discussions that require greater attention and effort because they don’t involve statements that have been practiced and refined over time. These are instances when you may let your guard down and make comments that you consider to be friendly conversation but which the patient perceives as offensive, inappropriate, or sexual in nature.

An extensive discussion of communication strategies and techniques is beyond the scope of this resource. Readers are encouraged to review the Patient Centred Communication E-learning Module for additional information.

Trauma is a lasting response that comes from living through an event or events involving an actual or perceived threat to a person’s psychological, emotional, or physical wellbeing.18 “Trauma occurs when an individual experiences an event such as sexual assault, physical injury, or the threat of death that they are unable to prevent, stop, or psychologically process.”19 Trauma can overwhelm a person’s ordinary coping mechanisms. It can interfere with their memory, their trust in the world around them, and their sense of self.18

Trauma can arise from a range of experiences. People can experience the same event and have different responses to it, with some people developing a trauma response as a result while others do not.20,21 Trauma fundamentally affects a person’s neurobiology and how memories are encoded. Neuroscience helps to explain people’s diverse responses when faced with danger and threat.22

When faced with a threat event, there are four common responses. Many people are familiar with fight and flight; however, two other responses, freeze and fawn, are also common.

- Fawn: Attempt to please the attacker to prevent being harmed.

- Fight: Display aggressive behaviours.

- Flight: Run and hide.

- Freeze: Stay still and quiet until danger/threat subsides.22, 23

These responses describe what happens in a person’s brain and body during the threatening event and immediately afterwards. These neurobiological responses affect memory, behaviour, thinking, and attention.

Trauma theory suggests that when traumatic memories aren’t fully processed, they become stored in the body as physical reactions to certain triggers—such as situations, sensations, or emotional states that remind a person of the trauma. Altered or impaired processing can cause unpredictable reactions to triggers that may not appear directly connected to the original event.19 “The physical and psychological nature of some traumatic events, places these patients at risk for experiencing distress during examinations or procedures… Memories of trauma can be easily triggered by physical health care examinations and procedures, and reexperiencing traumatic memories can “set off a cascade of negative feelings and emotions.””19

Instances of sexual abuse and sexual misconduct are often traumatic because they threaten a person in many ways. Sexual abuse and sexual misconduct can cause long-term physical, emotional, and psychological issues. In addition, severe, repeated, or prolonged stress all result in physiologic changes to the brain and altered mental health. The most common is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but depression, anxiety, substance abuse, or suicidality are also seen, sometimes in combination. These risks are increased if the person experienced prior trauma, lacks social support, or experiences negative responses to disclosure of the traumatic event.10

Trauma-Informed Practice

As previously stated, it is certain that you regularly work with survivors of sexual violence. With that in mind, it is imperative that you understand trauma, recognize the signs of trauma and dissociation, and implement trauma-informed practice as a universal precaution within their practice settings.

Four Key Elements to Trauma Informed Care:18

- Realizing the widespread impact of trauma and potential paths to recovery.

- Responding by integrating this knowledge into all aspects of a physiotherapy practice.

- Recognizing common reactions to trauma in patients and staff.

- Resisting re-traumatization by using principles of trauma-informed care.

Signs of past trauma/dissociation

It is not enough to simply tell the patient, “If you are uncomfortable, tell me.” After patient consent has been obtained you need to watch for non-verbal signs that the patient is no longer comfortable with what’s happening or has withdrawn consent. These signs may include, but are not limited to:

- Physical withdrawal

- Tense hands or body

- Shallow breathing

- Decreased responses to questions

- Appearing to disengage or “zone out”24

If you notice any of these signs, it is important to pause, check in with your patient, and reassess if you still have consent to proceed.

Adapting Your Practice

Patients may not disclose past experiences of sexual violence or other trauma. In some instances, they may be unwilling to discuss a trauma history. In other instances, the patient may have unconsciously repressed their trauma history.19 For these reasons, you are expected to take precautions during your interactions with all patients, to make sure that you don’t re-victimize patients while providing care.19 Approaching every patient with the assumption that they have experienced a history of trauma helps to protect the well-being of all patients.

Seminal work from Schacter, et al24 identified nine principles of sensitive practice based on the findings of research with adult survivors of sexual abuse. You can demonstrate sensitive practice by applying these principles during patient interactions.

Other sources have identified six principles of trauma-informed practice, which include:

- Awareness of trauma and the neurobiology of trauma

- Looking at trauma through the eyes of the patient

- Creating safety and trust during interactions

- Providing choice and supporting collaboration

- Focusing on strengths

- Patient empowerment18

The two models include significant overlap. When applied to physiotherapy practice, you can meaningfully enact these models and demonstrate trauma-informed, sensitive practice by:

- Engaging in continuing professional development about trauma and the neurobiology of trauma to further understand how trauma affects your patients, and how to adapt your practice (awareness and knowledge, understanding non-linear healing).

- Using plain language communication to ensure that your statements and the information you provide is as clear and understandable as possible (sharing information, creating safety and trust, patient empowerment).

- Intentionally communicating about everything that you are doing and why. Some may perceive this as over-communicating; however, clear communication is essential. Err on the side of saying more about what you are doing and why (taking time, sharing information, creating safety and trust).

- Using robust informed consent practices to ensure that ongoing patient consent is in place throughout every physiotherapy encounter (sharing control, respecting boundaries, choice and collaboration, patient empowerment).

- Monitoring your patient closely for signs of trauma or dissociation, or that consent has been withdrawn (sharing control, respecting boundaries, understanding non-linear healing, looking at trauma through the eyes of the patient).

Culturally Aware Care

A person’s culture and the communities to which they belong inherently effects their values, beliefs, ways of being in the world, and the decisions and choices they make. A person’s culture and identity affect what they consider normal, expected, or acceptable when interacting with other people. This is true for both the patient and the physiotherapist.

In relation to sexual abuse and sexual misconduct, it is worth considering:

- What the patient expects from their health care providers.

- Whether the patient has previously received physiotherapy services.

- What they understand about physiotherapy, including such things as the need to touch the patient’s body and the need to directly see the body area that is being treated.

You will also need to consider how a patient’s culture may affect their acceptance of you as their physiotherapist, the services you provide, and the patient’s perception of your comments and actions.

Cultural safety and culturally aware care is a broad topic that affects many aspects of physiotherapy practice. Readers are encouraged to review the Indigenous Cultural Safety, Health Equity and Anti-Discrimination guide for additional information.

While it can be helpful to understand some commonalities among members of different identifiable cultural groups, viewing patients as members of a group, rather than as individuals can lead to stereotyping and inappropriate assumptions.25

You will also need to reflect on:

- The norms, assumptions, and biases you bring to the therapeutic relationship.

- How these guide your actions and comments.

- Whether those norms and assumptions aide or impair your ability to develop therapeutic relationships and deliver care to the client that the client perceives as safe and appropriate.

Reflective practice is a critical element of providing equitable, culturally-safe care. This reflection may help to identify values, beliefs, and assumptions that could lead to comments or actions that are inconsistent with sexual abuse and sexual misconduct or other professional requirements.

In relation to sexual abuse and sexual misconduct and culturally aware care, you are encouraged to:25

- Acknowledge and reflect upon your own culture.

- Reflect on how the patient’s culture may affect how they perceive your comments and actions during the delivery of physiotherapy services.

- Consider how you can adjust your communication and actions to accommodate the patient’s background, expectations, and needs, with the goal of providing culturally-safe physiotherapy care.

Trauma Informed Care

- Alberta Health Services: Trauma Informed Care Learning Modules [eLearning series]

- Dr Gabor Mate: The 7 Impacts of Trauma [video]

- Bessel van der Kolk: The Body Keeps the Score [book]

- Bessel van der Kolk: How the body keeps the score on trauma [video]

- Bessel van der Kolk: Healing Trauma and How the Body Keeps the Score, How To Academy [YouTube Playlist]

Consent

- Consent Guide for Alberta Physiotherapists

- Consent eLearning Module

Therapeutic Relationships

- Therapeutic Relationships Guide for Alberta Physiotherapists

- Patient Centred Communication eLearning Module

- Government of Alberta. Health Professions Act, RSA 2000, c H-7, Available at https://canlii.ca/t/56jck. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- University of Alberta. Understanding Sexual Assault. Available at: https://www.ualberta.ca/current-students/ sexual-assault-centre/understanding-sexual-assault. Accessed February 18, 2019.

- Government of Canada. Gender-based Violence (GBV) Against Indigenous Peoples in Canada: A Snapshot. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/women-gender-equality/gender-based-violence/intergovernmental-collaboration/gbv-indigenous-peoples-snapshot.html. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- Ontario Coalition of Rape Crisis Centres. Recognizing the Expertise of Black, Indigenous and People of Color Communities in Sexual Violence Support Work and Violence Prevention. Available at https://sexualassaultsupport.ca/recognizing-the-expertise-of-black-indigenous-and-people-of-color-communities-in-sexual-violence-support-work-and-violence-prevention/. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- Ontario Coalition of Rape Crisis Centres. Supporting 2SLGBTQQIA+ Inclusion and Confronting Transphobia and Homophobia: OCRCC Responds. Available at https://sexualassaultsupport.ca/supporting-2slgbtqqia-inclusion-and-confronting-transphobia-and-homophobia-ocrcc-responds/. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- Government of Quebec. Consequences of Adult Sexual Assault. Available at: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/en/sexualassault/understanding-sexual-assault/consequences. Accessed February 15, 2019.

- RAINN. Effects of Sexual Violence. Available at: https://www. rainn.org/effects-sexual-violence. Accessed February 15, 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual Violence: Consequences. Available at: https://www.cdc. gov/violenceprevention/sexualviolence/consequences. html. Accessed February 15, 2019.

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Standards of Practice for Physiotherapists in Alberta. Available at https://www.cpta.ab.ca/for-physiotherapists/regulatory-expectations/standards-of-practice/. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Protecting Patients from Sexual Abuse and Sexual Misconduct eLearning Module. Available at https://www.cpta.ab.ca/for-physiotherapists/courses/cpta-protecting-patients-from-sexual-abuse-sexual-misconduct/. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Therapeutic Relationships Guide for Alberta Physiotherapists. Available at https://www.cpta.ab.ca/for-physiotherapists/resources/guides-and-guidelines/therapeutic-relationships-guide/. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- Epstein RM, Hundert EM. Defining and Assessing Professional Competence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2002;287:226–235.

- Sexual Assault Center of Edmonton. “Definitions: Feminism.” Available at: https://sace.ca/learn. Accessed February 15, 2019.

- Government of Alberta. Sexual Violence Prevention – Sexual Consent. Available at: https://www.alberta.ca/sexual-violence-prevention-sexual-consent. Accessed July 14, 2025.

- Province of Alberta. Alberta Hansard, Wednesday morning, October 31, 2018. Available at: https://www.assembly.ab.ca/assembly-business/transcripts/transcripts-by-type?legl=29&session=4#m. Accessed July 14, 2025.

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Consent Guide for Alberta Physiotherapists. Available at https://www.cpta.ab.ca/for-physiotherapists/resources/guides-and-guidelines/consent-guide/. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Patient Centred Communication eLearning Module. Available at https://www.cpta.ab.ca/for-physiotherapists/courses/patient-centered-communication/. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- AHS Trauma Training Initiative. Trauma Informed Care eLearning Modules 1-7. Available at https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/info/page15526.aspx. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- Reeves, E. A Synthesis of the Literature on Trauma-Informed Care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing; 36:9, 698-709.

- Mate G. The 7 Impacts of Trauma. [Video] Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O5jmsJAClpw. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- Van der Kolk. How the Body Keeps the Score on Trauma [Video]. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iTefkqYQz8g. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- Haskell L. Critical Foundations in Trauma-Informed Care. Presentation: CNAR Master Class, Ottawa, October 7, 2025.

- Knight, JD. Is the Nervous System Sympathetic. Journal of Surgery and Medical Case Reports. 2025, 2:2, 019. Available at https://surgery-medical-casereports.com/1/article/view/44/29. Accessed June 25, 2025.

- Schachter CL, Stalker CA, Teram E, Lasiuk GC, Danilkewich A. Handbook on Sensitive Practice for Health Care Practitioners: Lessons from adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. 2008. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada.

- College of Physiotherapists of Alberta. Indigenous Cultural Safety, Health Equity, & Anti-Discrimination Guide for Alberta Physiotherapists. Available at https://www.cpta.ab.ca/for-physiotherapists/resources/guides-and-guidelines/indigenous-cultural-safety-health-equity-anti-discrimination-guide/. Accessed June 25, 2025.